Daydream/Disorder

Aideen Gallagher (she/her)

This piece is a reflection on my adult ADHD diagnosis: what it has looked like, felt like, and meant for me and my family. I love to write as a way of understanding myself and my experiences, and so writing this has helped me digest and reflect on the way ADHD impacted my childhood. I hope that by sharing this I can help people understand what this experience may feel like for friends and family, or even inspire someone to seek help if they too struggle with their symptoms.

Naarm

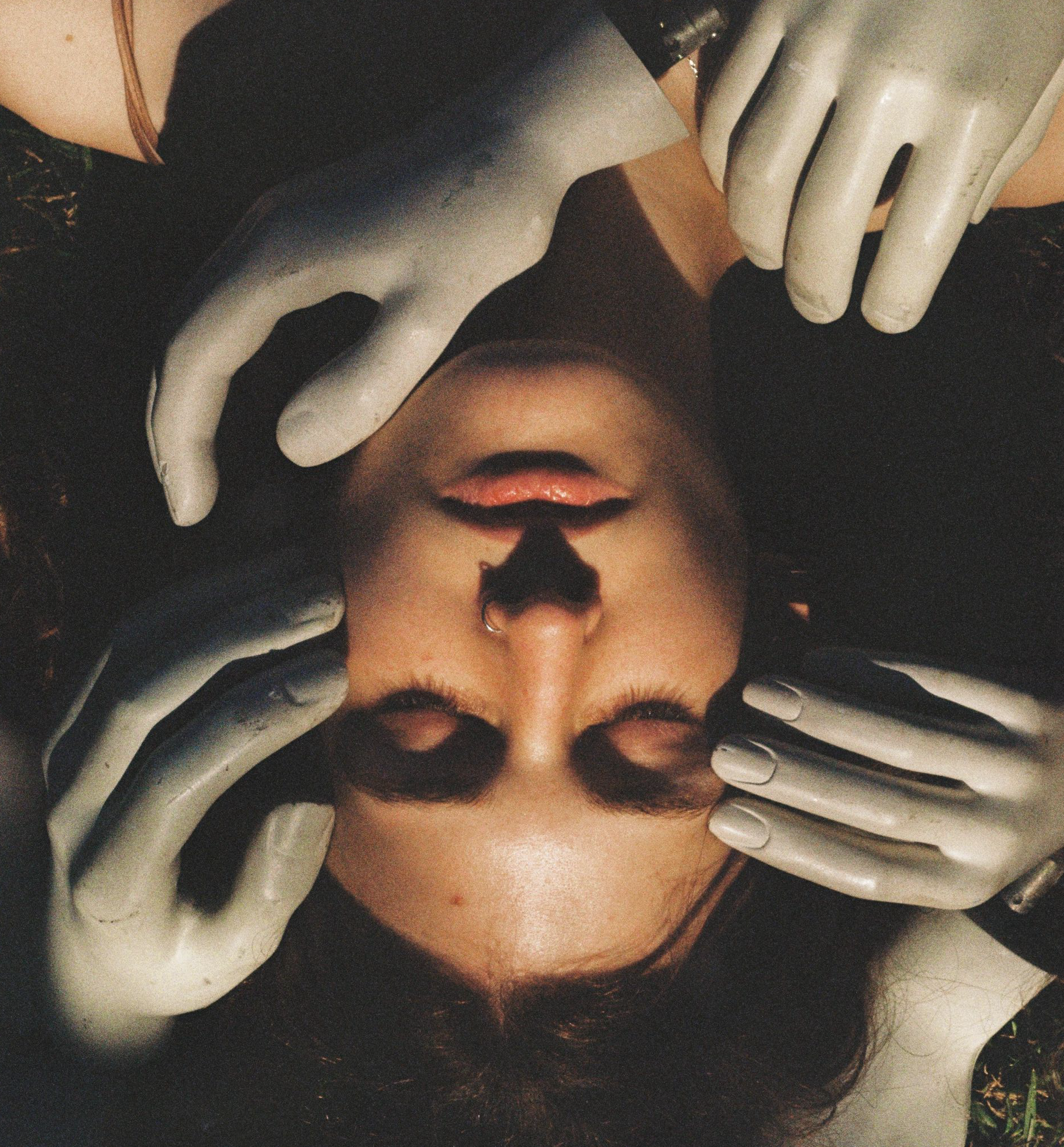

Cover image by Devika Suri @devikaa_

My most animated recollections from primary school are usually the ones where I was in deep trouble. Seething with embarrassment from my fingers into the back of my eyes, I’d swallow back my reheated tears.

The teacher told me to look her in the eye when she’s speaking, pay attention. So, I’d look her in the eyes - and I’d notice they were blue. Also slightly green, particularly near the middle, and they sat neatly upon a stary crest of flecked, almond freckles. Her lecture was stern but all I could notice was the way the window’s light fell silently across her temple and into her mouth, like it was feeding her.

She stopped speaking. I panic.

Alright, Aideen. Do you understand? Does that make sense? Aideen, you ask too many silly questions. You need to work on your listening skills.

I was a serious child. I’d lament, coming home from school I’d form a glassy picture in my mind of the type of student I wanted to be. Like Hannah or Jenny. They were neat, they were organised, they didn’t let the ink from their Texta pen drain though their school bags after losing the lids and the teachers liked them.

I don’t want this to sound as though I am full of self-pity for slipping through the gaping canyon that is under-diagnosis of female ADHD. It’s not as though I was particularly unfortunate, or underprivileged. To the contrary, I have been provided ample opportunity to develop adaptive tendencies around behaviours associated with my sprinkling of cognitive dysfunction.

Like many varieties of neurodiversity, generations past were much less aware of their existence or how they manifested between the sexes. The lack of recognition of symptoms in girls is due to a diagnostic criterion designed from presentation in males, plus parent-to-teacher referrals being spurred by rambunctious boys. I was not rambunctious, rather I was so unaware of my surroundings I would sometimes turn to the child next to me (teacher still mid-instruction, mouth agape, stares on with fury) and share my latest animal trivia. To an untrained eye this may have been a rude or potentially dim child. In the 1990s, scientists believed ADHD was as much as nine times as common in males than females. Today’s diagnosis rate is 2.5 males to every female.

Fast forward ten odd years: I’m now acutely aware of my spacey idiosyncrasies however not entirely free of it. That ditzy kid was almost as insufferable for the hospitality manager as it were my grade three math teacher. The hospitality industry can be a distinctive type of callous even for the neurotypical: a fast-paced, hierarchical marshland swimming with pompous cliental who prefer their oysters shucked to order and their staff treated poorly. My wandering mind was strung up and left swinging in a fine-dining Italian restaurant which needed you to learn on the job, walk faster, and keep busy. The summer I learned to cork fine wine and discreetly cry in the fridge room taught me tenacity, how to carry three plates, and to never be rude to service staff.

An eventual diagnosis felt like gazing blankly at a mirror minutes before recognising my own face. I was staring at myself for years but only now did the pieces fit together. As a bonus, the insight also helped translate the personalities and dynamics of my immediate family – a fiery household of emotive, resilient women who have a complex relationship with concentration.

The presumed inexistence of female ADHD in girls during the 1970’s meant people like my mum were to embrace the ‘quirks’ she supposedly had, and capitalise upon a life of hyperactivity, poor concentration, and a flighty, sensitive manner.

My mum is a remarkable woman. She refers now to some of her behaviours as being related to ADHD, but this was only after her children were diagnosed: exposing a trembling and raw hereditary thread. She describes herself as a kid who ‘could never sit still’. Incredibly, I was a child who refused to move. The polarisation in our personalities at this age is an ode to the beautiful spectrum of ADHD presentation.

Typically, hyperactive tendencies are seen more commonly in males than in females. ADHD is characterised as both attention deficiency and hyperactivity, but neither of these is necessary. Hyperactivity doesn’t just look like a crazed little boy gnawing playdough, either. It can feel like being unable to stop yourself from cutting people off when speaking about your favourite topic of conversation, or a deep uneasiness if you haven’t been for a run that day. Over time, symptoms, like people themselves, mature and change. The kid who couldn’t sit still might look very different as an adult who has internalised their impulsiveness. Women and people who are gender non-conforming are more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety and depression, as manifestations of ADHD, before the ADHD itself.

I consider myself to be on the attention deficient end of diagnosis, whilst my mum has an innate jitter. Her eyes follow your words and her body moves with her speech. She’s a runner, and a swimmer, and a steadfast mover. When I was a kid, she decided she would try open ocean water skiing. After growing up in rural Ireland, a pessimist might have doubted the likelihood of her winning any accolades in these bombastic Australian waves. But that’s what my mum always reminded me as a kid - it’s about being the optimist. The tune of her tone waning

- now Aideen, not necessarily -

rings like my personal motivational manta.

When I started studying at university, I was bewildered by the number of people who worked on ‘ground floor’ of the library. It was incomprehensible to me that anyone here was getting anything done whilst an absolute cacophony of conversation was enlivened around us. I was unable to work or to talk to friends when my mind would insist on tuning into all the other discussions in the room, like a renegade radio antenna. Vehemently I’d scurry away to the dead zone, a back corner in the lowest lumen environment of fourth floor where the sound of smacking bubble gum had the potential to cause my emotional unrest. On those days my mind would stream my daydreams with all the colour turned up. Sometimes the pictures were something so beautiful, it felt like a shame to thwart. I notice now that my best and most beautiful words appear to me when my mind is attempting to concentrate on something entirely different, as if these creative spin offs need the momentum of the mainstream focus to take flight.

The drugs now quiet my colourful slipstreams, helping me look ahead at the task on my screen. I am grateful and I am lucky. I want the ability to sit down and focus, I want to (sometimes) be the tidy student.

But before the medications, let’s support the ditsy girls. I hope more of them, lost in their glassy eyed window worlds, are given the leeway to be understood rather than reprimanded and the support they need to recognise they are capable. It’s not their fault their homework papers are always crumpled (and/or wet) and spelling makes no sense.

My ADHD has plenty to offer. Teary eyed but sincere, distracted but determined, disordered but creative. I’ll charge my army of competent, sensitive soldiers into battle; our hyperfixation pivoting chaotically until we achieve the heights of historical skill diversity (running, climbing, cycling etc).

There is wealth in embracing our neurodiversities - whether that be in ourselves, our colleagues, or our friends. Those colourful minds add rigour and light to our thinking and our conversations. I love what ADHD has given me, and the fantastic ways it has manifested in my family. I am still learning about my brain and what she’s capable of, and hope that more people have a similar opportunity with whatever tools they choose.